News Story

Due to long-term discrimination along the lines of race and gender, the classical music scene has commonly been dominated by white men. It has been difficult for women and people of colour to not only enter the world of classical music but also be credited and remembered as they deserve. As the musician Loraine James said in a recent article, ‘it’s not just an absence, it’s an erasure.’ For those who are both women and people of colour, it is even more difficult.

Over the past few years, there has been a surge in the rediscovery of composers and musicians who have been erased from history, and a move within the classical music industry to create a more inclusive and accessible path going forwards. We want to shine a light on three Black women who have made a huge impact in classical music, from the 1800s to the present day.

Florence Price

Florence Price was born in 1887 in Arkansas, educated at the New England Conservatory of Music and remained active in Chicago’s classical music scene until her death in 1953. Price was the first Black female composer to have a symphony performed by a major American orchestra, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra premiering her First Symphony in 1933. Despite this milestone, Price’s works have been overlooked, to the extent that a trove of her compositions were left languishing in her old Chicago summer home for years, only being rediscovered in 2009.

Price drew from her heritage in her work, infusing her pieces with African American folk idioms such as juba dances and arranging spirituals alongside symphonies. Yet, Price struggled to have her work performed due to the barriers she faced as a Black woman – writing in 1943 to the music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra she referred to herself as possessing ‘two handicaps—those of sex and race’. Meanwhile, her white contemporaries Dvorak and Gershwin received praise for the same practice of incorporating African American musical traditions into their pieces.

However, although the white classical music establishment may not have welcomed her with open arms, Price had supporters in other corners. In 1939, the legendary Black American contralto Marian Anderson performed Price’s arrangement of the spiritual ‘My Soul is Anchored in the Lord’ before 75,000 people at a historic concert at the Lincoln Memorial, after she was rejected from performing at Washington's Constitution Hall due to being Black. This performance become symbolic in the growing civil rights movement, with Price’s composition programmed as the concert finale.

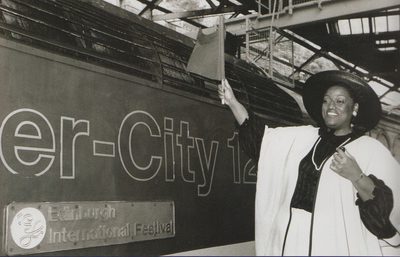

In recent years, Price has found another champion in the Music Director of The Philadelphia Orchestra, Yannick Nézet-Séguin. Speaking of his enthusiasm for performing Price’s work, Nézet-Séguin commented, ‘I think we in the music world have some catching up to do’, adding ‘It’s only possible because I truly love her music. Otherwise, I wouldn’t do it’. The Philadelphia Orchestra performed Price’s First Symphony at the Edinburgh International Festival this August, in a very belated Scottish premiere of the piece.

Jessye Norman

One of the most famous opera singers of all time, celebrated American soprano Jessye Norman was known for her emotional delivery and regal style. She was invited to perform at several presidential inaugurations, sang leading roles with major opera companies such as the Metropolitan Opera and was also a regular performer at the Festival throughout the 1970s and 80s.

Norman was a creative visionary, creating the concept for the extraordinary song cycle woman.life.song, for which she selected the writers Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison and Clarissa Pinkola Estés to write lyrics. Norman performed the premiere of the composition at the Carnegie Hall in 2000 before bringing it to the BBC Proms that year; it was next performed at the 2021 Festival by the Chineke! Orchestra.

When Norman was a child, she took inspiration from contralto Marian Anderson, who by the time Norman was 10 had become the first Black singer to appear at the Metropolitan Opera, in 1955. Norman herself inspired and continues to inspire the next generation of opera singers – when she died in 2019, Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess was being performed at the Met Opera, with a cast including award-winning singers Angel Blue and Golda Schultz. Schultz posted on Facebook: ‘We are here because she walked ahead and made the road a little less difficult’.

Chi-chi Nwanoku CBE

In 2015, British double bassist Chi-chi Nwanoku made history by founding the ground-breaking Chineke! Orchestra, Europe’s first majority-Black professional orchestra. In an interview with Classic FM last year, she reflected on her experiences leading up to this decision: ‘I’d already had a three-decade career in the classical industry and found myself the only person of colour on the stage, and not just on the stage but in the entire auditorium’. Dedicated to diversifying classical music, Chineke! both provides opportunities for musicians of colour in their professional and junior orchestras and platforms music by composers of colour.

Performing at the Festival in 2021 and 2022, Chineke! championed works from composers including Samuel Coleridge Taylor, a mixed-race British composer born in 1875, and contemporary Australian First Nations composer Valerie Coleman.

Chineke! continues to change the game for classical music, breaking boundaries and opening doors to underrepresented musicians and composers. Find out more about their upcoming concerts.

Which Black women in classical music inspire you? We would love to hear about them! Share your thoughts on social media using #EdIntFest.