Pictures at an Exhibition

Pictures at an Exhibition

Take a whistlestop round-the-world trip with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra and William Barton.

Joining the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra conducted by Jaime Martín, William Barton takes centre stage in Treaty by Deborah Cheetham Fraillon. Performed for the first time and composed for the Yidaki, the work evokes the depth and richness of Indigenous Australian culture.

Created by Indigenous communities in northern Australia at least 1000 years ago, the Yidaki is widely known by the anglicised term Didgeridoo. Its name varies across regions, languages and cultural knowledge.

Before reaching Australia, there’s a trip to Italy in Edward Elgar’s In the South. Written after an Italian holiday, Elgar said that he was inspired by ‘the thoughts and sensations of one beautiful afternoon’.

Then on to an art gallery, where Modest Mussorgsky acts as tour guide in Pictures at an Exhibition. Vividly orchestrated by Maurice Ravel, each movement evokes a portrait or landscape, from a clumsy gnome to the majestic Great Gates of Kyiv.

A rich and fulfilling auditory experience

Listen on Soundcloud or Spotify.

Programme

A keepsake freesheet is available at the venue for this performance.

Full programme

Elgar In the South, Op.50

Deborah Cheetham Fraillon Treaty for Yidaki and Orchestra

World Premiere

Mussorgsky arr. Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition

William Barton Kalkadungu Yurdu

WILLIAM BARTON ENCORE

Glinka Ruslan and Ludmila: Overture

MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ENCORE 1

Grainger Irish Tune from County Derry

MELBOURNE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ENCORE 2

Performers

CloseOpen

- Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

- Jaime MartínConductor

- William BartonYidaki

Melbourne Symphony OrchestraCloseOpen

- First ViolinNatalie Chee (concertmaster)

Tair Khisambeev (acting associate concertmaster)

Anne-Marie Johnson (acting assistant concertmaster)

Peter Edwards (assistant principal)

Sarah Curro

Peter Fellin

Deborah Goodall

Karla Hanna

Lorraine Hook

Kirstin Kenny

Michelle Ruffolo

Anna Skalova

Kathryn Taylor

Zoe Black

Jacqueline Edwards - Second ViolinMatthew Tomkins (principal)

Jos Jonker (associate principal)

Monica Curro (assistant principal)

Emily Beauchamp

Mary Allison

Isin Cakmakçioglu

Tiffany Cheng

Andrew Hall

Robert Macindoe

Philippa West

Patrick Wong

Roger Young

Michael Loftus-Hills - ViolaChristopher Moore (principal)

Lauren Brigden

Katharine Brockman

Anthony Chataway

William Clark

Aidan Filshie

Gabrielle Halloran

Jenny Khafagi

Fiona Sargeant

Ceridwen Davies

Isabel Morse - CelloDavid Berlin (principal)

Rachael Tobin (associate principal)

Rohan de Korte

Michelle Wood

Rebecca Proietto

Angela Sargeant

Caleb Wong

Jonathan Chim

Ariel Volovesky - Double BassJonathon Coco (principal)

Rohan Dasika (acting associate principal)

Ben Hanlon, (acting assistant principal)

Aurora Henrich

Stephen Newton

Luca Arcaro

Caitlin Bass - FlutePrudence Davis (principal)

Wendy Clarke (associate principal)

Sarah Beggs - PiccoloAndrew Macleod (principal)

- OboeJohannes Grosso (principal)

Michael Pisani (acting associate principal)

Ann Blackburn - Cor AnglaisDafydd Camp (guest principal)

- ClarinetDavid Thomas (principal)

Philip Arkinstall (associate principal)

Robin Henry - Bass ClarinetJonathan Craven (principal)

- BassoonJack Schiller (principal)

Elise Millman (associate principal)

Melissa Woodroffe - ContrabassoonBrock Imison (principal)

- HornNicolas Fleury (principal)

Andrew Young (guest associate principal)

Saul Lewis (principal third)

Josiah Kop

Abbey Edlin

Rachel Shaw - TrumpetOwen Morris (principal)

Shane Hooton (associate principal)

Rosie Turner

Daniel Henderson - TromboneJosé Milton Vieira (principal)

Richard Shirley - Bass TromboneMike Szabo (principal)

- TubaTimothy Buzbee (principal)

- TimpaniMark Robinson (guest principal)

- PercussionShaun Trubiano (principal)

John Arcaro

Robert Cossom

Hugh Tidy

Eugene Ughetti - HarpYinuo Mu (principal)

- CelesteLouisa Breen

- SaxophoneJustin Kenealy

Dive Deeper

Listen to The Warm Up: your audio introduction to the performance.

Programme Note

At the 2025 International Festival, we have commissioned a series of expert essays to help you Dive Deeper into your Festival experience.

This essay on Pictures at an Exhibition explores the movements of the suite and how the once-maligned composition came to be celebrated.

By Jessica Duchen

Jessica Duchen is a music critic, author and librettist. She contributes to The Times, the I Paper and BBC Music Magazine. Her latest book is the biography Myra Hess – National Treasure and her libretti include the award-winning opera Dalia with Roxanna Panufnik.

The Hideous Besides the Beautiful

Prodigiously gifted and wielding a distinctive style of musical ‘realism’, Modest Mussorgsky enjoyed a brief, brilliant flowering, only to die raddled by alcoholism aged 42.

His family had destined him for the military, but in 1858 he left that career to devote himself to music. Together with Alexander Borodin, Cesar Cui, Mily Balakirev and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, he became one of the so-called Mighty Handful or ‘the Five’. Following in the footsteps of Mikhail Glinka, they sought to create a distinctively Russian language, rooted in folksong and the music of the Orthodox Church.

What really inspired Mussorgsky, however, was the longing to capture life in all its aspects, the hideous besides the beautiful. In 1878, Pyotr Tchaikovsky observed: ‘Mussorgsky, for all his ugliness, speaks a new language. Beautiful it may not be, but it is fresh.’

Modest Mussorgsky, 1876

© Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainA Gallery of Movements

A hefty blow struck Mussorgsky in 1873: the death of a close friend, the artist Victor Hartmann, aged 39. The following year, the composer visited a retrospective exhibition of Hartmann’s works, organised by the art critic Vladimir Stasov at the Academy of Fine Arts in St Petersburg. It sparked the idea of capturing the images and his response to them in music. The result was Pictures at an Exhibition for solo piano, in which ten ‘pictures’ are linked by ‘promenades’.

It was published in a much-edited version by Rimsky-Korsakov in 1886, long after Mussorgsky’s death; only Ravel’s orchestration finally made it an audience favourite. This adaptation was commissioned by the conductor Serge Koussevitzky, although the work had enjoyed several earlier orchestrations. It had been much maligned by importunate pianists who considered Mussorgsky’s writing somehow deficient; but to Ravel, ‘Mussorgsky’s alleged incorrections are sheer strokes of genius’. Koussevitzky conducted its premiere in the Paris Opéra on 19 October 1922

Promenade The composition begins with a solitary melodic line, which is then harmonised. Stasov, who wrote summaries of each piece, noted that Mussorgsky depicts himself ‘roving through the exhibition, now leisurely, now briskly […] at times sadly, thinking of his departed friend.’

I. Gnomus shows a gnome on crooked legs, the grotesquery captured in strong dynamic contrasts, frequent pauses and limping rhythms.

Promenade A transition introduces the mysterious soundworld of the next picture.

II. The Old Castle. Stasov says: ‘A medieval castle before which a troubadour sings a song.’ An obsessive heartbeat rhythm underpins a mournful ballad, which Ravel entrusts to the saxophone.

Promenade A bridge towards a sunnier image:

III. Tuileries In Paris’s Tuileries garden, children scamper about, alternately amusing and plaintive. An abrupt change of mood leads into:

IV. Bydło A rough Polish ox-cart grinds over the mud, its driver singing. Ravel heightens with percussion a long crescendo and diminuendo as the vehicle approaches, passes and trundles away.

Promenade We travel from the heaviest image towards the lightest:

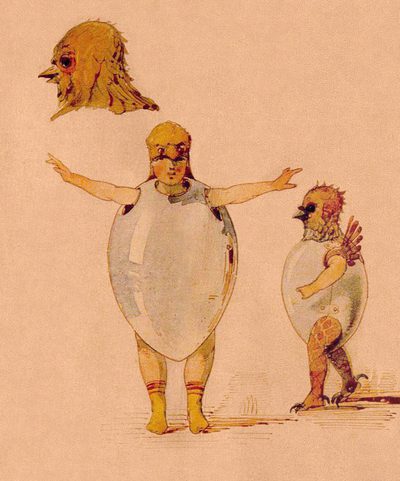

V. Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks Hartmann’s sketch was a design for the ballet Trilby or The Demon of the Heath at the Bolshoi in 1871. The chicks are canaries; the picture showed a child dancer with torso encased by an egg. Ravel provides a high-set, glistening orchestration.

Sketches of theatre costumes for the ballet Trilby by Viktor Hartmann

© Wikimedia Commons / Public DomainVI.‘Samuel’ Goldenberg and ‘Schmuÿle’ Stasov commented: ‘Two Jews, one rich, one poor’. Mussorgsky uses Hebraic melodic lines, respectively pompous and quavering. Vicious anti-Semitic prejudice was rife in Russia at the time, but here two Hartmann pictures are involved, the first a dignified portrait, the other heartbreakingly sorrowful. Mussorgsky owned both.

VII. Limoges The French town’s marketplace bustles with commerce, bartering and quarrelling. The pace ratchets up until there’s an abrupt stop:

VIII. Catacombs subtitled ‘With the Dead in a Dead Language’. Three figures holding a lantern stand by a dark cavern in Paris’s catacombs. Imposing chords alternate with hushed ones, suggesting distant echoes. The Promenade turns eerie. Stasov wrote: ‘The creative spirit of the dead Hartmann leads me towards the skulls, invokes them; the skulls begin to glow softly.’

IX. The Hut on Hen’s Legs (Baba Yaga) Hartmann’s picture is a clock carved with images from the legend of the witch Baba Yaga’s hut, but Mussorgsky brings us a demoniac vision of the inhabitant herself. Her witch’s ride leads into:

X. The Bogatyr Gates (or The Great Gate of Kiev) Stasov wrote: ‘Hartmann's sketch was his design for city gates at Kiev, in the ancient Russian massive style with a cupola shaped like a slavonic helmet.’ It was never built – but Mussorgsky conjures up the magnificent city, vivid with the pealing of Orthodox cathedral bells. In Kyiv, in more peaceful times, the air fills with virtually the same sounds.

A Work for the Ages

Mussorgsky did not live to see Pictures at an Exhibition rise to prominence. In due course, though, Ravel’s arrangement became a lynchpin in the repertoire of orchestras worldwide; the piano version has soared in commensurate popularity, while theatrical transformations have extended from ballets to animations. With its visionary imagination and wealth of character, this once-maligned composition has emerged, finally, as a work for the ages.

© Jessica Duchen, 2025