Bach & Bartók

Bach & Bartók

Budapest Festival Orchestra return to the Festival with a programme that celebrates their Hungarian heritage and showcases the vibrancy of music written for dance.

The Budapest Festival Orchestra and polymath founder-conductor Iván Fischer make a welcome return to Edinburgh after their popular 2023 performances. This programme pulses with the vibrant contrasts of dance – from the elegance of Baroque to the raw energy of modern ballet.

Johann Sebastian Bach's Orchestral Suite No.4 is an irresistibly lively take on a standard courtly form. Fischer echoes that sense of experiment in his own 21st-century Dance Suite for Violin and Orchestra, a Bach tribute that dances from bossa nova to ragtime, tango to boogie-woogie.

Béla Bartók's dramatic music for the 'pantomime grotesque' ballet, The Miraculous Mandarin was banned for 'moral filth' on its premiere in 1926. Based on the Hungarian writer Melchior Lengyel's shocking 1916 short story, the score lived on in an orchestral suite, shorn of its most controversial sections.

As a conductor, Iván Fischer, inspirational founder of the Budapest Festival Orchestra, has never hesitated to wear his heart on his sleeve, or to encourage his musicians to do likewise.

Listen on Soundcloud or Spotify.

Supported by James and Morag Anderson

Programme

A keepsake freesheet is available at the venue for this performance.

Full programme

Bach Orchestral Suite No.4 in D, BWV 1069 (1725)

20minsI. Ouverture

II. Bourrée I

III. Bourrée II

IV. Gavotte

V. Menuett I

VI. Menuett II

VII. Réjouissance

Iván Fischer Dance Suite for Violin and Orchestra, in memory of JS Bach (2024)

19minsI. Prelude

II. Bossa nova

III. Rag time

IV. Tango

V. Boogie woogie

UK PREMIERE

Bartók The Miraculous Mandarin, Op.19, Sz.73 (ballet) (1918–24)

33minsI. Allegro: Introduction

II. Moderato: First Decoy Game

III. Second Decoy Game

IV. Sostenuto: Third Decoy Game

V. Maestoso: The Mandarin Enters

VI. Allegro: The Girl Sinks Down to Embrace Him

VII. Sempre Vivo: The Tramps Leap Out

VIII. Adagio: Suddenly the Mandarin's Head Appears

IX. Agitato: Again, the Frightened Tramps Discuss How To Eliminate the Mandarin

X. Molto Moderato: The Body of the Mandarin Begins to Glow With a Greenish Blue Light

XI. Più Mosso: The Mandarin Falls On the Floor

Performers

CloseOpen

- Budapest Festival Orchestra

- Iván FischerConductor

- Guy BraunsteinViolin

Budapest Festival OrchestraCloseOpen

- ConductorIván Fischer

- 1st ViolinGuy Braunstein

Violetta Eckhardt

Ágnes Biró

Balázs Bujtor

Csaba Czenke

Mária Gál-Tamási

Emese Gulyás

Erika Illési

István Kádár

Péter Kostyál

Eszter Lesták Bedő

Gyöngyvér Oláh

János Pilz

Davide Dalpiaz - 2nd ViolinTímea Iván

Antónia Bodó

Solvejg Wilding

Pál Jász

Zsófia Lezsák

Noémi Molnár

Anikó Mózes

Levente Szaboó

Zsolt Szefcsik

Zsuzsanna Szlávik

Zoltán Tuska

Erika Kovács - ViolaCsaba Gálfi

Zoltán Fekete

Barna Juhász

Nikoletta Reinhardt

Nao Yamamoto

Cecília Bodolai

Krisztina Haják

Gábor Sipos

Zita Zarbók

Salomé Osca - CelloPéter Szabó

Éva Eckhardt

Lajos Dvorák

György Kertész

Gabriella Liptai

Kousay Mahdi

Orsolya Mód

Rita Sovány - Double BassZSolt Fejérvári

Attila Martos

Károly Kaszás

László Lévai

Csaba Sipos

Uxia Martinez Botana - FluteGabriella Pivon

Anett Jóföldi

Bernadett Nagy - OboeDudu Carmel

Eva Neuszerova

Marie-Noëlle Perreau

Michele Antonello

Andrea Mion

Elisabeth Passot - ClarinetÁkos Ács

Roland Csalló

Rudolf Szitka - BassoonAndrea Bressan

Dániel Tallián

Bálint Vértesi - HornZoltán Szőke

András Szabó

Máté Harangozó

Zsombor Nagy - TrumpetGergely Csikota

Tamás Póti

Zsolt Czeglédi

Mark Bennett - TromboneBalázs Szakszon

Attila Sztán

Gergely Janák - TubaJózsef Bazsinka

- TimpaniRoland Dénes

- PercussionLászló Herboly

István Kurcsák

Kornél Hencz

Ádám Maros

Nándor Weisz - HarpÁgnes Polónyi

- Celesta / Organ / Piano / Electric Piano / HarpsichordEmese Mali

László Adrián Nagy

Dóra Pétery

Dive Deeper

Listen to The Warm Up: your audio introduction to the performance.

Programme Note

By Sarah Urwin Jones

Sarah Urwin Jones is a writer, editor and translator specialising in Classical Music and Opera. She has written on music for The Times, The Independent and BBC Music Magazine amongst others and writes programme notes for a number of orchestras and opera houses.

Bach, Bartók and the Echoes of Dance

French culture was all the rage in early 18th-century Germany, inspired by the dazzling works of Jean Baptiste Lully, court composer to the dance-mad ‘Sun King’, Louis XIV at Versailles. Lully frequently contrived instrumental dance suites as court entertainment, using the overtures and ballet interludes from his operas. The music filtered quickly to Germany, where composers were keen to imitate the French style.

Orchestral Suite No.4 in D, Johann Sebastian Bach

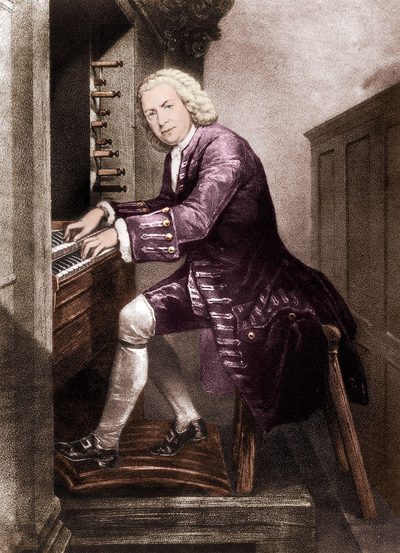

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750) developed the genre in his four Orchestral Suites (‘Ouvertures’), most likely composed between 1717, when he was working at the Cöthen court of Prince Leopold, north of Leipzig, and 1739, during his long tenure in Leipzig itself. The Orchestral Suite No 4, likely the first composed (the suites were numbered in the 20th Century), was probably compiled from earlier works rewritten for Leipzig’s Collegium Musicum.

Orchestrated for strings, harpsichord, wind (oboes and bassoon), trumpet and timpani (likely to be additions in a later version), it has the fullest orchestra of the four suites. The virtuosic writing, which vividly evokes dance movement, combines the refined ‘French’ form with elements of what Germans saw as the more ‘passionate’ Italian style.

The Overture has a sparkling instrumental back-and-forth, a dialogue which Bach reworked for his (Christmas) Cantata BWV 110 some years later. Three French dances follow: a Bourrée (a lively character piece that reflects the jumps in the dance itself), a Gavotte (vivid and inspired by folk dance) and a Minuet (reflecting the courtly version of a southern French folk dance). The finale is the doubly infectious Réjouissance, which is both highly complex, playing with rhythms and meter, and virtuosic.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750), German Composer

© Stefano Bianchetti / Bridgeman ImagesDance Suite, Ivan Fischer

Some few centuries later, Ivan Fischer’s Dance Suite, reverentially ascribed ‘in piam memoriam Bach’, was written by the Budapest Festival Orchestra Music Director after finding himself imagining the nostalgic feelings an elderly contemporary of Bach might have felt listening to the Orchestral suites with their references to French dances that were popular ‘in the previous generation’. It led Fischer to compose a suite ‘after’ Bach, comprising ‘a sequence of dances for which...people now may have the same type of nostalgia’.

Ivan Fischer (1951–present)

The Prelude opens with a Bachian yet freeform cadenza, the orchestra entering in somber mood, segueing into an off kilter waltz, before returning to the sombre solo theme. The first of the four dance movements proper is a Bossa Nova, lightening the mood before an infectious Ragtime, led by the flute and continued slightly off-key in the violin. The Tango is again flute-led, a hazy evocation of tango rhythms that dissipates as if in a dream. By way of finale – a modern-day reflection of Bach’s Réjouissance - a rambunctious Boogie-Woogie zips along with an ever-increasing roster of toe-tapping musicians.

TheMiraculous Mandarin, Béla Bartók

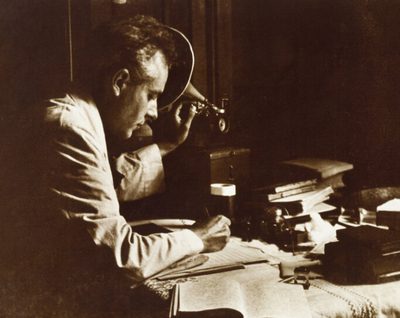

Dance of a different ilk in Béla Bartók’s one-act ‘grotesque pantomime’ The Miraculous Mandarin, controversial in his time and with a brutal plot that still shocks. Composed in 1918-1919, and orchestrated in 1924 to a story by Melchior Lengyel (who also penned Hollywood comedies), it is a gritty, sordid tale of a woman held hostage by three tramps and forced to lure men in to a room for the three to rob.

Written at a time of hardship and political upheaval in Hungary, not to mention a dose of Spanish Flu, Bartók’s thrillingly visceral music, with its violent rhythms and erotic undertones, charts a path in 12 sections from seduction to robbery and murder. When the ballet premiered to scandalised uproar in Cologne in 1926, the mayor banned further performances. But Bartók felt it a masterpiece.

Bela Bartok (1881–1945), Hungarian composer

© NPL - DeA Picture Library / Bridgeman ImagesComposed on the cusp of Bartók’s flirtation with atonality, each character is described in distinctive musical terms. The first two men that the woman (represented by the clarinet) lures in from the street are penniless – a shambling old man and a shy young man, and the robbers throw them out, represented in the score with thuggish staccato in the brass.

The third victim is the ‘Miraculous Mandarin’, chiming with a societal fascination with the East. Bartók used his knowledge of various Eastern tonalities to musically define the Mandarin. His entrance is marked with terrifying, almost supernatural grandeur in the orchestra, his instruments trombones, cymbals and drums. The woman is frightened by the Mandarin’s stare – the tentative music shows he too is unsure of the situation - but the robbers force her to dance for him. Overcome with passion, marked with increasing frenzy in the orchestra, the Mandarin chases the horrified woman. When he catches her, the men rob him and try to kill him, first by suffocating him, then running him through with an old sword, then hanging him from the light fitting.

But no matter what violence they inflict, he will not die, rising repeatedly towards the woman. After falling limp to the floor, he begins to glow a strange greenish-blue (marked with eerie moans from the chorus). The woman motions to the terrified men to set him free, and allows him to embrace her. Having done this, he dies, a symbol of the power of human passion, to juddering strains in the orchestra.

© Sarah Urwin Jones 2025